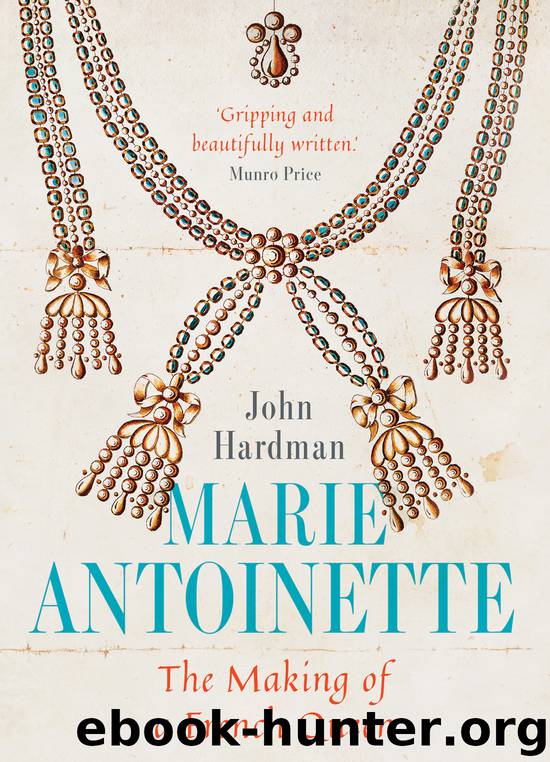

Marie-Antoinette by John Hardman

Author:John Hardman [Hardman, John]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780300243086

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

— EIGHT —

APPEASEMENT AND PLANS FOR

RESISTANCE

THE TUILERIES AND SAINT-CLOUD

THE NEW SITUATION: THE LOCATION OF POWER IN 1790

If Marie-Antoinette pursued a tortuous path it was because the Revolution itself was a maze. Or perhaps an apter image might be one of the complicated astronomical instruments of which the king was fond, maybe an orrery. Marie-Antoinette’s confidant, the comte de La Marck, had another image, that of Cartesian vortices in perpetual collision. In normal times, he said, you could analyse a political faction: how it worked, its aims and its methods, and deal with it accordingly. But in Revolutionary France you had 24 million Daltonian atoms perpetually colliding (they underestimated the population because of tax evasion). A man could be a mere instrument one day and a leader the next.1 The Revolution had introduced both social and political mobility. The underlying power was public opinion, which Necker had unleashed and which was stronger than any institution.

Since it was difficult to determine where real power lay, it was difficult for Marie-Antoinette to know whom to deal with, and in default of a disheartened king it was increasingly she who was doing the dealing. Much of this variable geometry concerned timing, which meant that by the time an early radical turned to the Court, his day was often done. In this volatile situation it was difficult to make promises stick; perhaps it was as dishonest to make them as to break them.

Theoretically, the National Assembly was the centre of everything since it had, in abbé de Siéyès’ phrase, ‘the dictatorship of constituent power’. It was the fons et origo, the God of Creation. In its early, heroic days, May–July 1789, the Assembly had spoken virtually with one voice as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, had he not died in 1778, would have wished. But by August the Assembly had split into several factions, though they would have eschewed a word that smacked of ancien régime intrigues. The main factions in the Assembly (from right to left) were: first, the ‘noirs’ or ‘purs’, who wanted a restoration of the ancien régime or as a minimum the Declaration of 23 June – some had emigrated, many would follow them; second, the monarchiens,2 who favoured a strong constitutional monarchy based on England’s; and third, what may be called the ‘soft left’, the logic of whose position was a republic, but who found it more comfortable and/or acceptable to keep Louis XVI as a figurehead deprived of any real power, executive or legislative.

These last were led by the ‘triumvirate’ of Adrien Duport, a former parlementaire, one of the few who had secured election to the Estates, Barnave and Alexandre de Lameth, one of the many disgruntled courtiers who were annoyed that Marie-Antoinette’s favours went to the Polignacs rather than to them.3 On the extreme left were men like Jérôme Pétion and Robespierre, though even as late as 1791 Robespierre said (darkly) that the declaration of a republic would be ‘aristocratic’. He believed that the Declaration of Rights should be the litmus test for all policy.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Military | Political |

| Presidents & Heads of State | Religious |

| Rich & Famous | Royalty |

| Social Activists |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37814)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23090)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19052)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18596)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13340)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12035)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8403)

Educated by Tara Westover(8059)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7492)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5852)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5641)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(5284)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5157)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5101)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4966)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4819)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4367)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4117)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3973)